WHERE HAVE YOU GONE, OLIVER STONE?— Part 2

From "Salvador" and "Platoon" to an Apologist for Putin

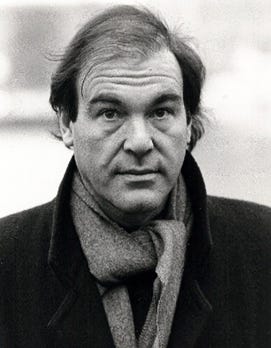

Oliver Stone, 1987 (photo Towpilot, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Stone in 2016 (photo Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before wrapping up his Castro trilogy with Fidel in Winter (2012), Oliver Stone had broadened the range of his despot docs with a film about Venezuela’s radical socialist president, Hugo Chávez: South of the Border (2009).

Besides extolling Chávez and his so-called Bolivarian Revolution, South of the Border’s wider agenda was to place him at the crest of the so-called “pink tide” of leftist leaders then sweeping Latin America. Besides Chávez, these included: Argentina’s former president Néstor Kirchner and his wife and successor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner; Bolivia’s Evo Morales; Brazil’s Lula da Silva; Cuba’s Raul Castro; Ecuador’s Rafael Correa; and Paraguay’s Fernando Lugo.

Following Fidel in Winter, Stone returned to Chávez with Mi amigo Hugo (2014), shot largely before and completed shortly after Chávez’s death from cancer in 2013. No mere polemic, as the title makes plain, it’s an unabashed homage to someone Stone had considered a close friend and with whom he’d bonded, he reveals in the film, because of their leftist politics but more deeply because of their mutual experiences as combat soldiers.

For those less taken with Chávez, however, the sheen of his “pink tide” promise had faded well before his death and would rub off completely under his handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro. The Washington Examiner’s Corey Franklin, for example, in 2017 called the Chavez bromance a “fulsome paean” and “cringeworthy,” especially in retrospect.[1] And as Venezuela’s situation worsened, so did the reviews. In 2019, Foreign Policy’s Jeffrey Taylor took off the gloves and, minus the hyperbole, echoed my assessment that Mi amigo Hugo is “a disgraceful tribute” that “whitewashes an authoritarian thug” and demonstrates that “Stone cannot be trusted to present the truth even when shooting documentaries about people who matter.”[2]

Further compromising Mi amigo Hugo, Stone’s “placing himself at the center of the interviews as a participant,” while not reaching Michael Moore proportions, turned the film from fluff piece into hagiography. Not content to simply give Saint Hugo the floor, Stone takes the stage himself in public forums as an honored guest of and cheerleader for the wanna-be heir apparent to legendary Latin American liberator Simón Bolivar.

In South of the Border, some of the effusive praise might still have been justified. Chávez was democratically elected and had made significant social reforms early on. But as has become a pattern for autocrats of the left and the right, he eventually abused his power to the detriment of democracy and the economy. Thus, in Mi amigo Hugo especially, but in his despot docs in general, Stone had come to function as what another colleague calls a “useful idiot”—someone who is naïvely being used by a controversial figure or cause to burnish their reputation.

Hugo Chávez, 2008 (photo Marcello Casal Jr./Abr, CC BY 3.0 br)

When questioned already after South of the Border about his uncritical take on Chávez, Stone’s defense was twofold: “He’s an underdog. I want to give him a fair shake.” Also, he was attempting “to right the balance of a heavily negative coverage” in the US media.[3]

And, of course, Stone had a point.

I’m the last person to deny, and have been vocal in decrying, the US’s appalling record of undermining democracy and supporting rightwing dictators in Latin America and beyond. But the immoral equivalency stops there.

As a child of the 60s, an anti-Vietnam War activist, and a leftist much like Stone, his championing of Chávez was a defining moment for me and marked a clear break with him politically. “When are we finally going to learn our lesson,” I lamented to my friends from the countercultural era, “about romanticizing authoritarian leftist ‘underdogs’?”

Stalin had poisoned the well for many Communists in the 1930s and 40s. And we should have gotten wise to Mao Zedong, whom I and many of my cohort idolized in the 1960s and 70s. I cringe to this day at having given a “Right on!” to Edward Albee’s 1967 play Quotations of Chairman Mao Tse-tung, which featured readings from Mao’s little red book as if it was holy writ.

Then along came Castro, and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, and then Chávez, and at least for me, the jig was up.

But not for Stone, who apparently still holds a torch for Hugo Chávez, and in 2017 added Vladimir Putin to his rogues’ gallery of documentary subjects in the four-part, four-hour Showtime series The Putin Interviews. Less so than in Looking for Fidel but similarly responding to the criticism of Putin since the 2014 annexation of Crimea and alleged 2016 election meddling, Stone does some hard-hitting in The Putin Interviews (based on conversations between 2015 and 2017) and even presses the Russian president on a few hot-button issues.

It’s simply not true, as some critics groused, that Stone is totally “non-combative” and doesn’t “push back,” and only half-true that the series intentionally set out to “humanize Putin and demonize America.”[4]

Stone owns the humanizing charge, saying that the thrashing he himself was sure to get from the US media would be “worth it to bring peace and consciousness to the world.” And Putin is actually, if disingenuously, quite generous toward America and, to Stone’s surprise, consistently calls the US “our partner.” To be sure, there’s a lot of lovey-dovey and softball stuff thrown in, but overall, Stone does not give Putin the kid gloves treatment.

There are some awkward moments, however, for both parties, which have been magnified in light of later events.

When Stone dutifully brings up Russia’s anti-LGBT law, Putin claims that gays are respected in the country and serve in the military. Then he puts his foot in it by admitting that he personally feels uncomfortable with gayness because it’s contrary to traditional family values and also harms Russia’s need to increase its birth rate. (Never heard that one before!)

Then they both make fools of themselves: first, when Stone responds that the anti-LGBT law “maybe seems sensible,” and second, when he jokingly asks how Putin would feel being in a shower with a gay man in the military, and they both laugh when Putin says this wouldn’t faze him because if the man made advances, his own mastery of judo could handle it.

Of course, Russia’s and Putin’s homophobia were no laughing matter then, and became anything but with the more draconian anti-LGBT law of 2022. As for Putin’s staunch assertions in the interviews of his respect for democracy and for Ukraine’s sovereignty, these lies became tragicomical when Putin was made “president for life” in 2020 and disastrous when Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2021.

(Courtesy of Showtime, Fair Use)

While one can’t blame Stone’s Interviews with Putin for having failed to realize his pipe dream of bringing peace to the world, several comments he’s made since the interviews and the Ukraine War have been startling, to say the least, and make one wonder whether he might truly have fallen off a cliff.

In April 2022, two months after Russia’s invasion, Stone presented JFK Revisited at the BCN Film Fest in Barcelona. When asked what his views about Putin were now, he doubled down his defense of the warmonger, just as his latest film was running interference for the conspiracy-riddled JFK: “It’s been three years since I last saw him, but the man I knew had nothing to do with the irresponsible and murderous madman that the media are now making him out to be, comparing him to Hitler and Stalin.” (“Useful idiot,” anyone?) Then, sounding like Sarah Cooper aping Trump, he added, “The Putin I knew was rational, calm, always acting in the best interest of the Russian people, a true son of Russia, a patriot, which does not mean a nationalist.”[5]

Stone concluded with a policy analysis that, as usual, blamed the US for the crisis and claimed that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was a pawn of the US in its goal “to turn Ukraine into a useful antagonist of Russia.”[6]

Since then, Stone has shifted his stance on the invasion, calling it “a mistake” and “wrong.” But he still couldn’t help couching this demurral in immorally equivalent terms, comparing Russia’s war against Ukraine to the US’s “many wars of aggression on its conscience,” before adding, “A dozen wrongs don’t make a right.”[7]

Then in May 2023, more than a year after the invasion, came another stunning pronouncement. In a promotional interview with The Guardian newspaper for Nuclear Now, Stone’s new documentary on nuclear power as the answer to climate change, he initially deflected talk of the war, saying, “I think Russia is doing a great job . . . with nuclear energy. China is also a leader in that field.” Then, flabbergastingly, he concluded, “Putin is a great leader for his country and the people love him.” And Joe Biden? He’s “a cold warrior in the worst sense of the word.”[8]

So, how does one make sense of Stone’s obtusely stubborn double standard toward the US?

It’s hard to avoid starting with his Vietnam War experience, and his early films on the subject. These were surely one way of dealing with the PTSD that any war inflicts to some degree on those who are given license to kill other human beings, who are in constant fear for their own lives, and who form strong bonds with their fellow soldiers and then watch them die or be maimed for life.

But for those who went into the war as gung-ho patriots, like Stone and Ron Kovic and others that I know, their nightmarish anxiety and profound sadness are compounded by intense guilt when they come to understand that the war they were led to believe was justified—a war that left tens of thousands of Americans and millions of Vietnamese dead or severely injured, with ongoing devastation from trip mines and environmental disaster—was not only for naught but wholly unjustified.

The sense of betrayal in such a case, especially for a young person in their formative years, must have been enormous. And to make matters worse for Stone, the national betrayal had been preceded by a familial one: his parents’ divorce, when he was 16, which left him, an only child, “a victim of his parents’ betrayal of each other” and of him.[9]

This deep-seated guilt and sense of betrayal, I believe, is the heart of darkness behind Stone’s obsessively portraying the US government, its military and intelligence sectors, the lackey portion of the media, and the Big Money behind them all, as the bad guys.

But in Putin’s case, it turns out, another more practical factor might have come into play.

Tucked into the tiny “Family” section in Stone’s Wikipedia entry is a brief reference to a BuzzFeed News article from 2015 with huge implications for Stone’s attitude and actions toward the Russian dictator.

According to the article, one of Stone’s two sons, Sean Stone (b. 1984), began co-hosting a new cable TV show in early 2015 with former Minnesota governor Jessie Ventura’s son, Tyrel (b. 1979)—and not just on any network but on the Russian government-backed, Washington, DC-based RT America (RT standing for “Russia Today”). Sean and Tyrel, who’d previously co-hosted a show for TheLip.tv network, replaced Abby Martin, who’d taken flak for criticizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Adding another quirky twist, Martin’s show had featured conspiracy theories and, BuzzFeed’s Rosie Gray claimed at the time, “RT’s move to give Ventura and Stone a show indicates that they are not planning to move in a different direction.”[10]

Wouldn’t it seem likely that RT’s move, at least in regard to Sean Stone, was also influenced by his being the son of the notorious Putin apologist Oliver Stone? And that reciprocally, Oliver Stone would’ve been even more prone to follow a pro-Putin line with his son working for a Russian government-backed TV network? And that Putin himself would be further encouraged to commit to Stone’s interviews the very same year?

Almost as bizarre as these “coincidences” is that nothing online, that I could find, bothers to connect the dots.

That Sean Stone’s relationship with his father was extremely close is indicated by his having appeared in almost all his father’s films, from Salvador in 1986 when he was two years old through the Wall Street sequel in 2010. He also narrated three 2005 documentaries on the making of his father’s epic 2004 film Alexander (16% Rotten Tomatoes rating), before branching out on his own as an actor.

Sean Stone, 2012 (photo سید حسن موسوی, CC BY 4.0)

Sean’s RT America show, “Watching the Hawks” (one presumes referring to US cold warriors, not the majestic birds) lasted until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. And in his last RT America telecast, guess what?

He chided celebrities for speaking out against the invasion, repeated a false claim that Oprah Winfrey had removed Tolstoy’s War and Peace from her Book Club, and last not least, said it was wrong to refer to Vladimir Putin as “some kind of dictator.”[11]

Must’ve made his father proud.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Thanks to Maria Elena de las Carreras, Jonathan Kuntz, Steve Mamber, and Ken Windrum for their input.

[1] Corey Franklin, “The deafening silence of Hollywood’s Chavistas,” Washington Examiner, May 1, 2017, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/the-deafening-silence-of-hollywoods-chavistas.

[2] Jeffrey Taylor, “Oliver Stone’s Disgraceful Tribute to Hugo Chávez,” FP, May 13, 2014, https://www.foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/13/oliver-stones-disgraceful-tribute-to-hugo-chavez.

[3] Andrew Goldman, “Rewriting History—Again,” The New York Times Magazine, November 25, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/25/11/magazine/olvier-stone-rewrites-history-again.html; Robert Smith, “Oliver Stone Profiles Power South of the Border,” NPR, September 25, 2009, https://npr.org/2009/04/25/113204260/oliver-stone-profiles-power-south-of-the-border.

[4] Ken Tucker, “Oliver Stone’s ‘Putin Interviews’ Are Fascinating Ego Trips,” yahoo!entertainment, June 12, 2017, https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/putin-oliver-stone-showtime-review-162809170.html; Verne Gray, “‘The Putin Interviews’ Review: Stone humanizes Russia’s Vladimir Putin,” Newsday, June 12, 2017, https://www.newsday/tv/the-putin-interviews-review-oliver-stone-humanizes-russias-vladimir-putin-k00972; Marlow Stern, “The Putin Interviews: Oliver Stone’s Wildly Irresponsible Love Letter to Vladimir Putin,” The Daily Beast, June 6, 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-putin-interviews-oliver-stones-wildly-irresponsible-love-letter-to-vladimir-putin.

[5] Jacinto Anton, “Oliver Stone: ‘The Putin I knew was rational, calm, always acting in the best interest of the Russian people,” elpais, April 26, 2022, https://english.elpais.com/2022/04/26/the-putin-i-knew-was-rational-calm-always-acting-in-the-interest-of-the-russian-people.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Pjotr Sauer, “Support for Putin among western celebrities drains away over Ukraine,” The Guardian, April 11, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/11/vladimir-putin-celebrities-ukraine-invasion-steven-segal-gerard-depardieu.

[8] Lauren Mechling, “Putin is a great leader for his country,” The Guardian, May 2, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/may/01/oliver-stone-documentary-nuclear-power-putin-biden.

[9] James N. Giglio, “Oliver Stone’s ‘JFK’ in Historical Perspective,” Perspectives on History, April 21, 1992, https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/april-1992/oliver-stones-jfk-in-historical-perspective.

[10] Rosie Gray, “Jesse Ventura’s Son And Oliver Stone’s Son Get A Show At Russia Today,” March 9, 2015, BussFeed News, https://www.buzzfeed.com/rosiegray/jesse-venturas-son-and-oliver-stones-get-a-show-at-russia-to.

[11] Cecilia Kang, “What It Was Like to Work for Russian State Television,” The New York Times, March 12, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/12/business/rt-america-russian-tv.html.